Artificial intelligence (AI) has generated increasing interest in “future of work” discussions in recent years as the technology has achieved superhuman performance in a range of valuable tasks, ranging from manufacturing to radiology to legal contracts. With that said, though, it has been difficult to get a specific read on AI’s implications on the labor market.

In part because the technologies have not yet been widely adopted, previous analyses have had to rely either on case studies or subjective assessments by experts to determine which occupations might be susceptible to a takeover by AI algorithms. What’s more, most research has concentrated on an undifferentiated array of “automation” technologies including robotics, software, and AI all at once. The result has been a lot of discussion—but not a lot of clarity—about AI, with prognostications that range from the utopian to the apocalyptic.

Given that, the analysis presented here demonstrates a new way to identify the kinds of tasks and occupations likely to be affected by AI’s machine learning capabilities, rather than automation’s robotics and software impacts on the economy. By employing a novel technique developed by Stanford University Ph.D. candidate Michael Webb, the new report establishes job exposure levels by analyzing the overlap between AI-related patents and job descriptions. In this way, the following paper homes in on the impacts of AI specifically and does it by studying empirical statistical associations as opposed to expert forecasting.

Artificial intelligence: What it is and how we’re measuring it

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an increasingly powerful form of digital automation, based on machines that can learn, reason, and act for themselves. Measuring it is hard because it is multifarious and emergent.

AI consists of a diverse set of technologies that serve a variety of purposes. Therefore, no single definition can yet capture its full set of operations and capabilities. However, broadly speaking, AI involves programming computers to do things which—if done by humans—would be said to require “intelligence,” whether it be planning, learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, or prediction.

Contrary to other forms of automation, such as robotics and software, researchers have had little time to learn about AI’s primary use cases in the economy.

To circumvent many of the problems posed by AI for labor market analysis then, this brief leverages a novel method created by Stanford Ph.D. candidate Michael Webb to quantify the exposure of occupations to AI, in order to assess the broader labor market impacts. (See Michael Webb, “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Labor Market.”)

Along these lines, the present analysis uses machine learning in the form of natural language processing to quantify the overlap between text from patents filed for AI technologies, and job descriptions from the U.S. Department of Labor’s O*NET database.

This process allowed Webb to generate a measure of every occupation’s varying levels of “exposure to AI applications in the near future.” These scores were then normalized to aid in comparing them with one another. As a result, “exposure” scores in this paper do not indicate the percentage of tasks that can be replaced by AI, but rather indicate each job’s relative exposure above (positive numbers) or below (negative numbers) the average job’s exposure to AI.

Read more about what AI is and how we’re measuring it on page 5 of the full report. »

Findings

In contrast to past analyses, this report finds that better paid professionals and bigger, high-tech metro areas are the most exposed to AI.

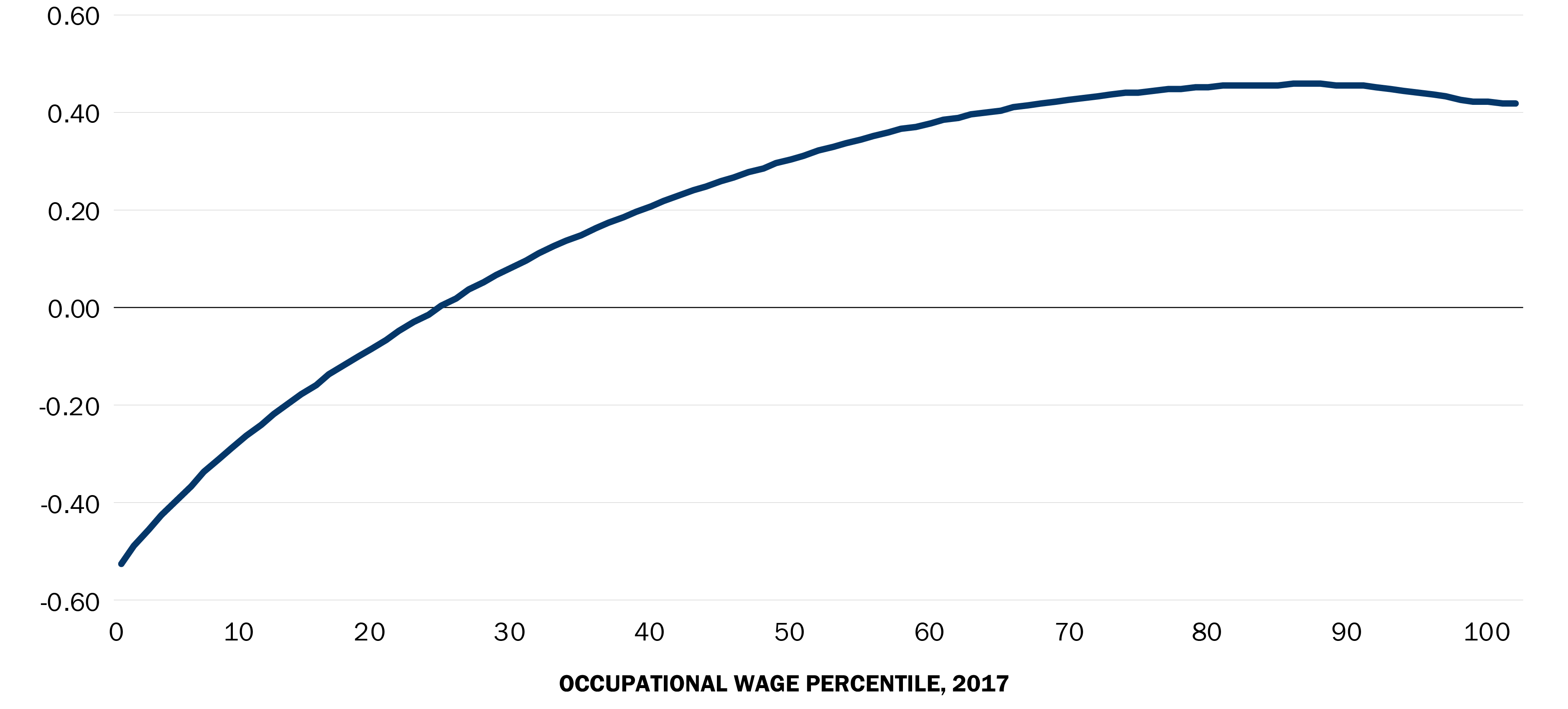

White-collar jobs (better-paid professionals with bachelor’s degrees) along with production workers may be most susceptible to AI’s spread into the economy

AI could affect work in virtually every occupational group. However, whereas research on automation’s robotics and software continues to show that less-educated, lower-wage workers may be most exposed to displacement, the present analysis suggests that better-educated, better-paid workers (along with manufacturing and production workers) will be the most affected by the new AI technologies, with some exceptions.

Our analysis shows that workers with graduate or professional degrees will be almost four times as exposed to AI as workers with just a high school degree. Holders of bachelor’s degrees will be the most exposed by education level, more than five times as exposed to AI than workers with just a high school degree.

White collar jobs may be most exposed to AI’s spread

Average standardized exposure by wage percentile of all occupations, 2017

Source: Brookings analysis of Webb (2019)

Our analysis shows that AI will be a significant factor in the future work lives of relatively well-paid managers, supervisors, and analysts. Also exposed are factory workers, who are increasingly well-educated in many occupations as well as heavily involved with AI on the shop floor. AI may be much less of a factor in the work of most lower-paid service workers.

AI could affect virtually every occupational group

Distribution of AI exposure scores for all detailed occupations in the United States by major occupational group, 2017

Source: Brookings analysis of Webb (2019)

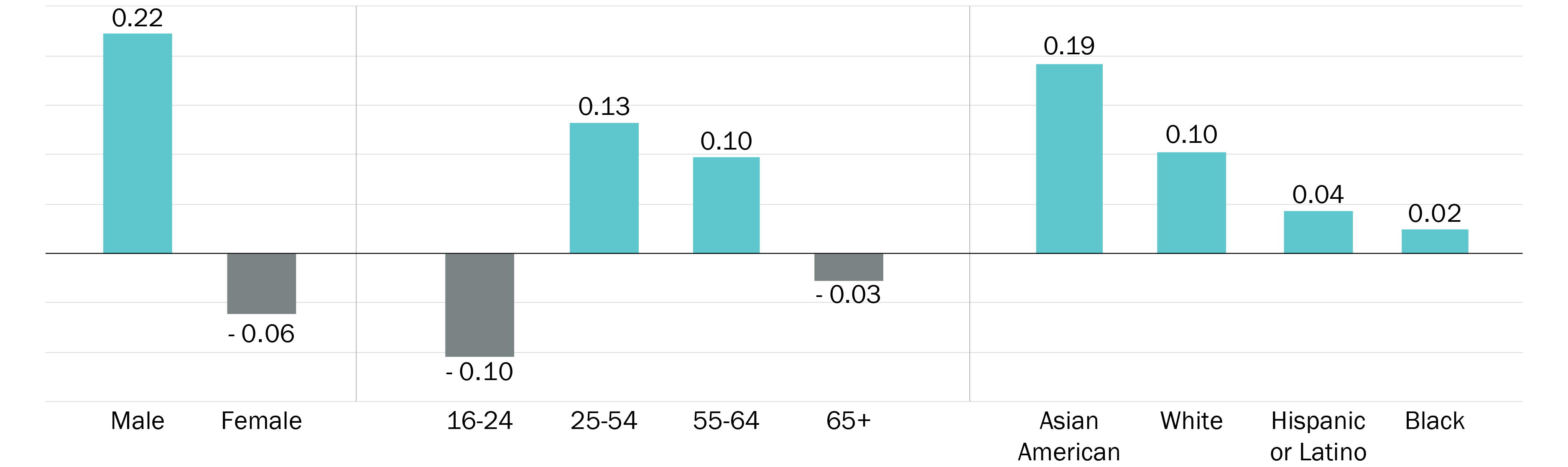

Men, prime-age workers, and white and Asian American workers may be the most affected by AI

Men, who are overrepresented in both analytic-technical and professional roles (as well as production), work in occupations with much higher AI exposure scores. Meanwhile, women’s heavy involvement in “interpersonal” education, health care support, and personal care services appears to shelter them. This both tracks with and accentuates the finding from our earlier automation analysis.

AI may not spare any demographic, but exposure levels will vary

Average standardize AI exposure by sex, age, and race-ethnicity, 2017

American Indians and Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and people indicating they are two or more races are not shown due to limited data availability.

Source: Brookings analysis of Webb (2019)

Bigger, higher-tech metro areas and communities heavily involved in manufacturing are likely to experience the most AI-related disruption

While AI will be employed virtually everywhere, its inroads will vary across space, determined by the local industry, education, and occupational mix. Contrary to the automation susceptibility maps, the present AI analysis reveals that smaller, more rural communities are significantly less exposed to technological disruption than larger, denser urban ones. This likely reflects the basic urban geography of the information, technology, and professional-managerial economy, with its orientation toward analytics, prediction, and strategy—all susceptible to AI. With that said, multiple metros and rural areas in the Heartland will likely contend with widespread AI given their orientation to agricultural, production, extraction, and transportation work.

Larger, denser urban communities—as well as Heartland metros—are more exposed to AI

Average standardized AI exposure by metro or NECTA, 2017

Source: Brookings analysis of Webb (2019)

Implications

While this assessment predicts which places and sectors will be impacted by AI, how these impacts play out is still an open question.

In conclusion, past “automation” analyses—including our own—have likely obscured AI’s distinctive impact. Yet here too much is an open question. Most notably, this brief quantifies only the potential exposure of occupations to AI—not whether adoption has occurred or how it will affect the completion of work.

In this regard, while the present assessment predicts areas of work in which some kind of impact is expected, it doesn’t specifically predict whether AI will substitute for existing work, complement it, or create entirely new work for humans.

That means much more inquiry—qualitative and empirical—is needed to tease out AI’s special genius and coming impacts.

This post was originally published by Metropolitan Policy program.